Abstract

Ethiopia is one of the countries where a wide variety of traditional fermented beverages are produced and consumed for a long time. Traditional fermented beverages are indigenous & popular to a particular area and have been developed by the people using age-old techniques from locally available raw materials in southern parts of country. In this study, maize, barely, sorghum were used as ingredients respectively. Some of Ethiopian indigenous traditional fermented beverages products are borde, booka and korefe, in which fermentation is natural and involves mixed cultures of microbes. The most common fermenting microorganisms, lactic acid bacteria and yeast, are used as a catalyst, for improvement of nutritional quality, good organoleptic properties, and safety were used. The moisture, ash, protein, fat, CHO and energy ranged from 78.9 – 83.4, 0.97 -4.8, 7.3 – 9.75, 6.71 – 2.33, 2.31 – 5.47 and 78.05 – 125.95% for all samples respectively. The result of microbial activities such as E. coli, Enterobacteriaceae, Lactobacillus and coliforms in borde, korefe and booka drink were 0.51, 1.67 ×101, 1.2 ×104, and 3.67 ×105 respectively. The nature of beverage preparation in Ethiopia, traditional household processing, associated lower microorganisms with a fermented beverage, and their contribution toward improvement. Therefore, this study shows that the alcoholic contents booka (1.53±0.2) < korefe (4.21±0.2) < borede (4.67±0.2), this is due to the fermenting time during preparation. In the future, to improve its quality, it is important to standardize the methods of beverage fermentation processes and advanced technologies.

1. Introduction

In many parts of Africa, villagers prepare fermented beverages from maize, sorghum, millet, barley or from various mixtures of these cereals. There is some information on the fermentation of a variety of African beverages such as Pito, Burkutu and Obiolor from Nigeria, Kaffir or Bantu beer from southern Africa, Merissa from Sudan, Busaa from Kenya and Cheka, Shamita, Tella from Ethiopia

| [1] | Mogessie A., and Tetemke M., (2019). Some microbiological and nutritional properties of Borde and Shamita, traditional Ethiopian fermented beverages. Ethiopian Journals of Healthy Development. 1-6. https://doi.org/10.314/sinet.v25i1.18076 |

[1]

.

Fermented beverages are an essential part of diets in all regions of the world and comprise about one-third of the worldwide consumption of food and 20–40% (by weight) of individual diets. It constitutes a major part of the diet in all parts of the world in addition to their role in social functions

| [2] | Niguse H., and Jedala R., (2020). Ethiopian Indigenous Traditional Fermented Beverage: The Role of the Microorganisms toward Nutritional and Safety Value of Fermented Beverage, International Journals of Microbiology, 12(3), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8891259 |

[2]

.

In Ethiopia, indigenous processing methods of Ethiopian fermented beverage are different from locality to locality or from product to product. Among the Ethiopian indigenous fermented beverages, Tella, Areki, Borde, Keribo, Shamita, Booka, and Cheka are produced and consumed. The fermented beverage such as Teji, Tella, and Areki are considered alcoholic, whereas Cheka, Korefe, Shamita, Keribo, Borde, and Booka are considered as nonalcoholic beverages

| [2] | Niguse H., and Jedala R., (2020). Ethiopian Indigenous Traditional Fermented Beverage: The Role of the Microorganisms toward Nutritional and Safety Value of Fermented Beverage, International Journals of Microbiology, 12(3), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8891259 |

[2]

. In Ethiopia, indigenous fermented beverages constitute a major portion of the diet of traditional Ethiopian homes, besides also consumed in different occasions such as holiday, wedding ceremony, and Iqub (a form of traditional revolving saving in which people voluntarily join a group and make a mandatory contribution every week or pay a month)

| [3] | Amabye, T. G., (2015). Evaluation of phytochemical, chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial screening parameters of rhamnus prinoides (Gesho) available in the market of mekelle, tigray, Ethiopia. Nat. Prod. Chem. Res., 3, 6. https://doi.org/10.472/2224--68361000199 |

[3]

. Their relative cheapness has a selective effect by providing a cheap alternative for the low income groups of consumers.

“Gesho” (Rhamnus Prinoides L.), also known as “dog wood”, is the most common ingredient used to prepare Ethiopian alcoholic beverages, primarily as a flavoring and bittering agent. The substance β-sorigenin-8-O-β-D-glucoside (“Geshoidin”) is the naphthalene compound responsible for imparting bitterness. In addition to this, it is also a source of fermentative microorganisms and plays a significant role during fermentation in regulating the microbial dynamic

| [3] | Amabye, T. G., (2015). Evaluation of phytochemical, chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial screening parameters of rhamnus prinoides (Gesho) available in the market of mekelle, tigray, Ethiopia. Nat. Prod. Chem. Res., 3, 6. https://doi.org/10.472/2224--68361000199 |

[3]

.

Alcoholic fermentation marks in the production of ethanol and yeasts are the major organisms. Lactic acid fermentation is produced by the presence of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) & Acetobacter species. Alkali fermentation frequently takes place through the fermentation of fish and seeds, popularly known as a condiment

| [2] | Niguse H., and Jedala R., (2020). Ethiopian Indigenous Traditional Fermented Beverage: The Role of the Microorganisms toward Nutritional and Safety Value of Fermented Beverage, International Journals of Microbiology, 12(3), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8891259 |

[2]

. Most of the Ethiopian local fermented beverages are products of the acid-alcohol type of fermentation. The nature of the preparation of fermented beverages in Ethiopia is not complex and does not require expensive equipment. The preparation of many local fermented beverages is still practiced at the household level under uncontrolled conditions, using rudimentary equipment such as empty oil vats and earthen vessels, and the handling and consumption often take place under conditions of poor hygiene

.

The advantageous effects related with fermented products have a special prominence during the production of these products in unindustrialized countries like Ethiopia. These effects resulted in decreased miss of raw materials, minimized cooking time, enhancement of protein quality and carbohydrate digestibility, upgraded bioavailability of micronutrients and removal of toxic and anti-nutritional factors. In addition, the probiotic effects and the low rate of pathogenic bacteria seen in fermented food and beverage products are especially important when it comes to undeveloped countries where fermented foods and have been stated to reduce the severity of diarrhea. Thus, a better understanding of the intestinal microbial populations will contribute to the development of new strategies for the anticipation and/or treatment of several diseases

| [5] | Almad D. C, Almada C, Martinez R, Sant’ana A., (2015). Characterization of the intestinal microbiota and its interaction with probiotics and health impacts. Appl. Microbial. Technol. 99: 4175- 4199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-015-6582-5 |

[5]

.

Availability of low cost foods produced using local knowledge and resources could contribute to enhance dietary diversity, particularly in low income families. Alemu T. and Aschalew N. (2022) indicated that, economic capability is one of the major factors for lack of dietary diversity among lactating women in Aksum town of Northern Ethiopia

| [6] | Alemu T., and Aschalew N., (2022). Preparations and Types of Local Traditional Alcoholic Beverage (Tella) in Amhara Region, Amhara, Ethiopia, Journals of Grug Research, 11, 1.8. https://doi.org/10.4303/jdar/236173 |

[6]

.

For better dietary diversity, it is good to have scientific information about nutritional composition and health promoting factors of locally made foods. In this regard, several studies have been conducted to determine the nutritional compositions of different types of local fermented foods in Ethiopia. However, the physicochemical properties, nutritional composition, bioactive contents, and antioxidant capacity of Korefe, Borde, Booka, Shameta” commonly consumed by lactating mothers of Konso, Derash, Burji, Oromo community not yet scientifically addressed. Therefore, this study aimed to determine proximate compositions, minerals contents, and anti-nutritional factors. The information generated from this study can be used to guide the local community and other stakeholders on the beneficial use of the product through further optimization of ingredients and fermentation conditions for better nutrition, strength

| [7] | Abegaz, K, Beyene F., and Langsrud, T., Narvhus, JA., (2002). Indigenous processing methods and raw materials of borde, an Ethiopian traditional fermented beverage. J Food Technol Afr. 59-64. https://dx.doi.org/10.4314/jfta.v7i2.19246 |

[7]

.

1.1. Some Traditional Fermented Beverages in Ethiopia

Fermented beverages constitute a major part of the diet of traditional African homes serving the fermented beverages are consumed in different occasions such as marriage, naming and rain making ceremonies, at festivals and social gatherings, at burial ceremonies and settling disputes. They are also used as medicines for fever and other ailments by adding barks or stems of certain plants

| [8] | Getachew T., (2015). A review on Traditional Fermented Beverages of Ethiopian, Journal of Natural Sciences Research. 5915): 94 – 102. https://doi.org/10.1079/5432 |

[8]

.

Fermented beverages produced from cereals usually referred to as beers while those produced from fruits are classified as wines. Microorganisms of various groups appear to be involved in the fermentation of beverages indigenous to different parts of the world. The sources of the microorganisms are usually the ingredients and the traditional utensils used for fermentation processes. Initially, therefore, a wide variety of microorganism are involved but most give way to more adaptive genera as the fermentation goes on. It may, thus be said that the initiation of fermentation of most traditional fermented beverages may be undertaken by different groups of microorganisms as far as sufficient fermentable sugars are available in the substrate. As the fermentation proceeds and the environment becomes more and more acidic, yeasts and lactic acid bacteria dominate the fermentation. These two groups of microorganisms usually determine the alcohol content and flavor of the final product

| [9] | Pederson, SC., (2009). Microbiology of Fermentation. 2nd ed. AVI Publishing Co. Inc. West Port. Connecticut. Rashid Abafita Abawari (2013). Microbiology of Keribo Fermentation: An Ethiopian Traditional Fermented Beverage. Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences. 16: 1113-1121. |

[9]

.

Korefe: is the name of the indigenous traditional fermented beverage made in Begemder province among the Koumant ethnic group and in Guji Oromo in Ethiopia. Dehusked barley is left in water overnight and toasted and milled. It is mixed with water and dried Gesho leaves and fermented in a clay container for 2 -3 months. When the beverage is needed, a small quantity of the mixture is taken, more water is added, and after a day’s fermentation, the beverage is ready for consumption. Yeasts are organisms that are responsible for the fermentation process of Korefe. The beverage alcoholic contents of Korefe ranged from 4.08% v/v to 5.44% v/v

| [7] | Abegaz, K, Beyene F., and Langsrud, T., Narvhus, JA., (2002). Indigenous processing methods and raw materials of borde, an Ethiopian traditional fermented beverage. J Food Technol Afr. 59-64. https://dx.doi.org/10.4314/jfta.v7i2.19246 |

[7]

.

Borde is traditional fermented beverages. It is a popular meal replacement in Southern Ethiopia and western parts of the country

| [10] | Blandino, A., Al-Aseeria, ME., Pandiellaa, SS., Canterob, D. Webba, C., (2003). Review: Cereal-based fermented foods and beverages. Food Res. Int. 36: 527–543 Desta, B (1977). A survey of the alcoholic contents of traditional beverages. Ethiop. Med. J. 15: 65-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0963-9969(03)00009-7 |

[10]

. Borde is considered to be a low alcoholic beverage 3.35 ± 0.64 (% v/v) mean value. People believe that Borde enhances lactation, and mothers are encouraged to drink substantial amounts of it after giving birth. It appears that the ingredients for Borde fermentation vary among Borde-producing communities. Maize, wheat, barley, sorghum, tef, were reported to be the major ingredient of Borde preparation in Southern Ethiopia. The major equipment used for the preparation of Borde are earthenware pots and griddle, grinding stones, bowls, and wonnfit (a sieve with a mesh of interwoven grass-fiber threads at the bottom) However, the processing steps are not markedly different. For malt preparation, barley is cleansed to remove dirt and extraneous materials and steeped in water for about a day. Excess water is drained off, and the soaked barley is allowed to germinate for five days wrapped in tanks or banana leaves. Later, germination barley can be sun-dried and ground finely. The whole mixture is put into the earthen jar and further blended in tap water. The starter is added and sealed well with plastic films and cloth and allowed to ferment at ambient temperature for 24 hours

| [11] | Fite, A., Tadesse, A., Urga, K., and Seyoum, E., (1991). Methanol, fuel oil and ethanol contents of some Ethiopian traditional alcoholic beverages. SINET. Ethiop J Sci. 14, 19-27. |

[11]

.

“Booka” is also an indigenous traditional fermented beverage in South Ethiopia, particularly consumed in Guji communities. Booka is the first animal origin traditional fermented beverage. It is a liquid slightly yellowish made of “Booka” from cow bladder, so the product is named as Booka. Booka is found sometimes at the bottom of “Buttee” (a traditional instrument that is used to ferment milk). However, the one that is used to ferment beverage (Booka) is usually from cow bladder. Equipment such as wooden bowl (Qorii), cup (Kookkii), container (Gan), and filters are used, whereas ingredients such as honey, sugar (sometimes), Booka from cattle bladder, and water are used. People of all ages including infants, pregnant, and lactating women drink Booka

| [12] | Girum T., Eden E., and Mogessie A., (2005). Assessment of the antimicrobial activity of lactic acid bacteria isolated from Borde and Shamita, traditional Ethiopian fermented beverages, on some food-borne pathogens and Ethiop. Journals of Biological Science. 5(2). |

[12]

.

1.2. Substrates for Beverage

In the preparation of wines from the starchy raw materials such as wheat, barley, rice, or corn, the raw materials must be degraded into sugars to ferment them by yeasts. Thus, traditionally fermented beverages throughout the world could be grouped into two main categories based on the types of substrates used for their preparation and production of ethyl alcohol. The first group of fermented alcoholic beverages in which sugars are the principal fermentable carbohydrates includes Ethiopian Teji, Borde, Booka, Korefe

| [13] | Mejıalor DJ. and Marshall E., (2012). Traditional Fermented Food and Beverages for Improved Livelihood, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy. |

[13]

and others such as Indian jack fruit wine, Mexican pulque, and Kenyan urawaya. The second principal fermentable carbohydrate is starch. For the fermentation process to occur, the starch should be hydrolyzed into simple sugars. Such hydrolysis could be achieved by malting or by using amylolytic molds and yeasts

| [14] | FAO, M. Battcock, and S. Azam-Ali, Fermented Fruits and Vegetables: A Global Perspective, FAO Agricultural Services Bulletin, Rome, Ethiopia and Italy, 1998. |

[14]

.

1.3. Fermentation and Importance of Microorganisms in Fermented Beverages

1.3.1. Improvement of Organoleptic Properties

Microbial fermentation makes the fermented beverage palatable as there will be an improvement on the organoleptic properties, texture, aroma, and flavor. Fermentation of borde, booka, korefe relies on the microorganisms (LAB and yeast), and their metabolic products contribute to acidity and also add distinctive flavor and aroma to the fermenting material. LAB isolated from various fermented foods produces organic acids and a high diversity of antimicrobial agents, which are responsible for the upkeep of quality and the palatability of fermented foods

| [15] | Debela T., Abel Z., Fitfte M., and Getaye A., (2018). “Production, optimization, and characterization of Ethiopian traditional fermented beverage “Tella” from barley,” Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research. 5(4): 797– 799. |

[15]

.

According to the finding by

| [16] | Mulaw G., Muleta D., Tesfaye A., and Sisay T. (2020). “Protective effect of potential probiotic strains from fermented Ethiopian food against Salmonella typhimurium DT 104 in mice,” International Journal of Microbiology, Article ID 7523629, 8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/7523629 |

[16]

, after 10 days of fermentation, tella becomes more acidic to consume due to the growth of Acetobacter spp., which converts ethanol to acetic acid under anaerobic conditions. The organoleptic properties of the fermented beverage make them more important, since it has wider acceptance.

1.3.2. Use as Probiotics

Probiotics are usually defined as microbial food supplements with beneficial effects on consumers. Probiotics have a great potential for improving nutrition, soothing intestinal disorders, improving the immune system, optimizing gut ecology, and promoting overall health because of their ability to compete with pathogens for adhesion sites, to antagonize pathogens, or to modulate the host’s immune response, pharmaceutical preparations, and functional foods for the betterment of public health. In many communities around the world, there are traditional beliefs that some fermented foods or beverages have medicinal value. Hence, rural communities are known to be consuming fermented beverages such as Borde, Booka, which they derive health benefits

| [17] | Lee M., Regu M., and Seleshe S., (2015). Uniqueness of Ethiopian traditional alcoholic beverage of plant origin, Tella. Journal of Ethnic Foods. 2(3): 110–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jef.2015.08.002 |

[17]

.

Most probiotic products contain LAB and molds that have been found to produce antibiotics and bacteriocins. The LAB belongs to the genera Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Enterococcus, Lactococcus, Streptococcus, and Leuconostoc, and Lactobacillus plantarum strain CIP 103151, Lactobacillus paracasei strain NBRC 15889, and Lactobacillus plantarum strain JCM 1149, inherently present in fermented Borde and Shamita, have antimicrobial properties against various foodborne pathogens invading the gastrointestinal tract

| [18] | Akinrele IA., (1970). Fermentation studies on maize during the preparation of a traditional African starch-cake food. Journals of Science and Food Agriculture. 21, 619¬. https://doi.org/10.12691/ajfst-2-5-3 |

[18]

.

1.4. Nutritional Qualities of Booka, Borde and Korefe in Ethiopia

Fermentation processes increase the digestibility and availability of nutrients. The enzymes such as amylase, proteases, lipases, and phytates modify the primary food products through hydrolysis of polysaccharides, phytates, proteins, and lipids. The number of proteins, carbohydrates and the water-soluble vitamins increase, while the ant nutrient factors (ANFs) in the foods decline during fermentation. Palm wine in West Africa is high in vitamin B 12, which is very important for people with low meat intake and for who subsist primarily on a vegetarian diet, idli (a LAB fermented product consumed in India) is high in thiamine and riboflavin as mentioned in

.

Lactic acid fermentation of cereals has been used as a strategy to decrease the content of ant nutrients, such as phytate and tannins. This leads to increased bioavailability of micronutrients such as zinc, calcium, phosphorous iron, and amino acids. The high microbial load of yeast and lactic acid bacteria qualify Borde as a good source of microbial protein

.

1.5. Prospects of Ethiopian Traditional Fermented Beverage

Based on the important role played by the traditional African fermented beverages, the consumers tend to recognize these beverages. Fermentation may be the most simple and economical way of improving cereal nutritional value, sensory properties, and functional qualities available at the local community level. In general, the fermented beverage is a promise in feeding additional segments of the increasing Ethiopian population in the future

| [21] | Lachenmeier, D.; Haupt, S.; Schulz, K., (2008). Defining maximum levels of higher alcohols in alcoholic beverages and surrogate alcohol products. Regular Toxicology Pharmacology. 50, 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2007.12.008 |

[21]

.

1.6. Objectives

Therefore, the objective this study was to compare their organoleptic, microbial and nutritional properties of alcoholic beverages of local drinking, Koref, Booka and Borde.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of Study Area

This study was conducted in Bule Hora town which was the capital town of the West Guji zone in the Oromia region. It was located on the paved Addis Ababa-Moyale highway and was found 467 far apart from Addis Ababa. It is the largest town in this zone mainly inhabited by the Guji Oromo and currently has 8 (eight) kebeles namely “Ardaa Biyyaa”, “Burqituu Midhiddii”, “Bulee Qaanyaa”, “Gooroo Guddinaa”, “Ejersa Fooraa”, “Bulee Qilxaa”, “Qachaa Yaa’aa”, “Gooroo Abbayyii”. It has a latitude and longitude of 5°35′N 38°15′E and an altitude of 1716 meters above sea level [BHWAO, 2019].

Figure 1. Location map of study area (Source: Google map).

2.2. Collection and Preparation of Samples

Laboratory based experiment was conducted from September 2023 to November 11/26/2023 to study microbial dynamics, nutritional values or properties and organoleptic evaluation during fermentation of korefe, borde and booka. 27 samples (1200 ml each) were collected in sterile bottles randomly from Korefe, Borde & Booka vendors at three localities in Southern part of Ethiopia, West Guji town (Bule Hora), Konso and Burji. After transportation of the samples (1.5 to 9 h), microbiological analysis, pH and ethanol content, protein, vitamins, carbohydrates, tastes, aroma, flavors, colors were immediately determined in the laboratory.

2.3. Experimental Methods and Design

2.3.1. Traditional Preparation of Korefe

The raw materials utilized for Korefe were barley, Gesho and water. The proportion of the malted and non-malted barley and Gesho was different among Korefe vendors, but, the method was used in the laboratory for Korefe preparation were; 15 kg of non-malted roasted barley (local name Derekot), 2.6 kg non- malted unroasted barley (Kita) and 1.5 kg malted non- roasted barley (Bikel, local name for malt) and 1 kg of Gesho powder. Step 1 is called Tigit includes both

I & II; In stage I, 4 g Gesho was mixed with 25 ml water and left at ambient temperature in a clean Erlenmeyer flask for 72 h. This was an initiation stage for the extraction of the flavor, aroma, bitterness and antibiotic from Gesho.

In stage II, 4 g Bikel powder was added with 45 ml water and fermented for 12 h. This was the first step for the real fermentation process.

In stage III, 12 g non-malted barley bread (Kitta) and 30 ml water were added and fermented for 48 h. The semisolid mixture formed at this stage is known as Tinsis.

In stage IV, 75 g roasted non-malted barley powder (Derekot) and 30 ml water was added and fermented for 72 h. The semisolid mixture formed at this step is known as Liwes. Then (1: 3 ratio) of Korefe and water was mixed after the end of fermentation and foam was formed. Formation of foam indicates that the beverage is ready for consumption

| [22] | Alemu H., Abegaz B. M., Bezabih M., (2007). Electrochemical behaviour and voltammetry determination of geshoidin and its spectrophotometric and antioxidant properties in aqueous buffer solutions, Bulletin Chemical Society Ethiopia. 21, 189-204. https://doi.org/10.4314/bcse.v21i2.21198 |

[22]

.

Three phase fermentation of Korefe In stage I, 4.5 g Gesho and 4.5 g Bikel powder was mixed with 67.5 ml water and left at ambient temperature in a clean Erlenmeyer flask for 72 h. This was the first fermentation process of Korefe and an initiation stage for the extraction of flavor, aroma, bitterness and antibiotic substances of Gesho. During the process a brown semisolid mixture called Tinsis was formed. In stage II, 13.5g non-malted barley bread (Kitta) and 30 ml water was added and fermented for 72 h. The semisolid mixture formed at this stage is known as Tinsis. In phase III, 76.5g roasted non-malted barley powder (Derekot) and 30 ml water was added and fermented for 48 h. The semisolid mixture formed during this stage is known as Liwes. Then a small quantity of the mixture was taken, water was added (1: 3 ratio) after the end of fermentation, foam was formed (

Figure 2)

| [23] | Teshome BE., Bikila NO., Abite BE. and Habtamu FG., (2018). Processing Methods, Physical Properties and Proximate Analysis of Fermented Beverage of Honey Wine Booka in Gujii, Ethiopia, Journal of Nutrition & Food Sciences 8(2): 1 -9. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-9600.1000669 |

[23]

.

Figure 2. Traditional fermented products of Korefe.

2.3.2. Traditional Preparation of Booka

For Booka preparation the researcher has investigated three-day period for observation and record of data in each district. On the first day the sample of Booka were observed carefully and according to the instruction from the elders the pure honey who’s purchased from local market were added then left for the coming day (

Figure 3). On the second day the observation regarding the colour change, fermentation and progress were recorded within 6 hours interval. On the last day the supernatant of Booka was carefully removed and after two to three-time dilutions it was made ready for the consumers

| [22] | Alemu H., Abegaz B. M., Bezabih M., (2007). Electrochemical behaviour and voltammetry determination of geshoidin and its spectrophotometric and antioxidant properties in aqueous buffer solutions, Bulletin Chemical Society Ethiopia. 21, 189-204. https://doi.org/10.4314/bcse.v21i2.21198 |

[22]

.

Figure 3. Traditional fermented products of Booka.

2.3.3. Traditional Preparation of Borde

Borde is prepared mainly from maize. 30 kg of maize flour is soaked in excess water and then deeply roasted in a hot flat metal pan. After cooling for about 30 min, about 250 g of malt is thoroughly mixed into clay container and blended in 30 L of boiling water. At this stage, 15 kg of ground barley whipped in hot water is added to it and allowed to ferment overnight. 2 L of Borde from a previous fermentation is usually added as starter. In the morning, the whole fermenting mixture is filtered using wire sieves and the filtrate is served for consumption. Depending on the preference of consumers, ground chili (Capsicum minimum) may be added to it at serving (

Figure 4 &

5). Borde is a very popular meal replacement which is consumed while at an active stage of fermentation. An average worker consumes about 3 L of borde in the morning. This is enough to keep him for most of the day without any additional meal

| [24] | American Association of Cereal Chemists (AACC). (2000). Approved method of the AACC (10th ed.). Saint Paul, MN: Author. |

[24]

.

Figure 5. Traditionally prepared Borde from maize (24).

2.4. Nutritional Analysis of Korefe, Booka and Borde Sample

During the fermentation process, korefe, booka and borde sample were taken aseptically at 24 h intervals and analyzed for nutritional analysis characteristics. The proximate composition of samples like moisture content, ash content, crude protein, crude fat, and crude fiber was analyzed on dry weight basis according to American Association of Cereal Chemists (AACC) (2000)

| [24] | American Association of Cereal Chemists (AACC). (2000). Approved method of the AACC (10th ed.). Saint Paul, MN: Author. |

[24]

.

2.5. Microbiological Analysis of Korefe, Booka and Borde Samples

During the fermentation process, Korefe, Booka and Borde sample was taken aseptically at 24 h intervals and analyzed for microbiological load in each phase for three samples separately. The pH was measured using a digital pH meter after calibration at 25 °C using buffers of pH 4 and 7. The pH of thick sample was measured after blending with distilled water at a 1: 1 ratio (w/v) into thick slurry at 24 h interval in each phase of fermentation. For titratable acidity, 5 ml sample was mixed with 20 ml of distilled water. From the mixture, 3-5 drops of phenolphthalein indicator was added. The solution was titrated against 0.5 N NaOH for each of korefe, borde and booka samples separately

| [7] | Abegaz, K, Beyene F., and Langsrud, T., Narvhus, JA., (2002). Indigenous processing methods and raw materials of borde, an Ethiopian traditional fermented beverage. J Food Technol Afr. 59-64. https://dx.doi.org/10.4314/jfta.v7i2.19246 |

[7]

.

An hydrometer was used to determine the alcoholic content (ethanol) of Koref, Booka and Borde standardized by using the alcohol determination of samples of known alcohol content. The liquid is poured into a tall jar, and the hydrometer is gently lowered into the liquid until it floats freely. This had conducted by taking a sample of National alcohol product found in the Laboratory of National Alcohol and Liquor Factory (LNALF)

| [22] | Alemu H., Abegaz B. M., Bezabih M., (2007). Electrochemical behaviour and voltammetry determination of geshoidin and its spectrophotometric and antioxidant properties in aqueous buffer solutions, Bulletin Chemical Society Ethiopia. 21, 189-204. https://doi.org/10.4314/bcse.v21i2.21198 |

| [25] | Kunyanga C., Mbugua S., Kangethe E., and Imungi J., (2009). Microbiological and acidity changes during the traditional production of kirario: an indigenous Kenyan fermented porridge produced from green maize and millet. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development. 9: 107-116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11816-018-0468-9 |

[22, 25]

.

In this study, identification of E. coli, LAB, S. aurous, Bacillus Spp. were carried out using the following procedures. The E. coli, LAB, S. aurous, Bacillus Spp. isolates were characterized using a microscope. All isolates under examination were separately cultured twice in de Man-Rogosa-Sharpe (MRS) broth and an overnight culture was used for all tests and incubated. Each sample was initially examined for colony and cell morphologies, cell grouping and motility as well as gram reaction using microscope test was undertaken. Growth at different temperatures was observed in MRS broth after incubation at 5, 15, 20, 35 and 45

oC for 120 h – 240 h. Growth in the presence of 4%, 8% and 9.6% NaCl was performed in MRS broth and incubated at 30

0C for 120 h. The growth of E. coli, LAB, S. aurous, Bacillus Spp. on acidic and basic media was checked by MRS broth media using HCl and NaOH

| [26] | Gergesenes T., (1978). Rapid method for distinction of gram-negative from gram-positive bacteria. European Journal of Applied Microbiology. 5: 123-127. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00498806 |

[26]

. The ability of fermentation by each isolate was evaluated by looking for the formation of gas (CO

2) in Durham’s tube

| [27] | Yohannes T, Fekadu M, Khalid S., (2013). Preparation and physiochemical analysis of some Ethiopian traditional alcoholic beverages. African Journals of Food Science. 7: 399 - 403. https;//doi.org/10.11648/j.ijhnm.20200602.13 |

[27]

.

2.6. Organoleptic Analysis of Korefe, Booka and Borde Samples

A questionnaire was distributed for a total

10 (ten) elder people whose had indigenous knowledge on Korefe, Borde and Booka preparation and whose had consumed them for at least three consecutive years. As well as 30 participants was selected to provide information on characteristics of them those available during data collection at market place. In addition to ten ender people three mothers whose prepared booka, koref and borde for at least two years were added as study participants to explain the preparation of them

.

Organoleptic properties were analyzed using five-point Hedonic scale (5-Excellent, 4-Good, 3-Average, 2-Fair, 1-Poor). The samples prepared from each were presented in coded form. The order of presentation of samples to the panel was randomized. Tap water was provided to rinse the mouth between evaluations. The panelists were instructed to evaluate the coded samples for color, taste, aroma, bitters, flavors, and overall acceptability.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 16.0. Means and standard deviations of the triplicates analysis were calculated using analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine the significant differences between the means followed by Duncan’s Multiple range test (p ≤ 0.05) when the F test demonstrated significance. The statistically significant difference was defined as p < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussions

Nutritional composition, microbial activities and organoleptic analysis of fermented borde, korefe and booka were presented in

Tables 1, 2 and 3. All the measurements for each parameter are measured by employing triplicate measurement and evaluated statistically by one-way ANOVA. The statistical data mostly obtained in this current study had shown better consistent results with permissible limits. Similarly, most of the Nutritional composition, microbial activities and organoleptic analysis of fermented Borde, Korefe and Booka had significant differences, evident through p < 0.05 as shown in tables below.

3.1. Nutritional Properties of Borde, Korefe and Booka

The moisture contents of borde, korefe and booka were 78.9±0.2, 92.1±0.2 and 83.4±0.2 which were higher than in study reported in Kappes SM, Schmidt SJ, Lee SY, 2007) indicated that the mean values of retail dry sausages moisture content values ranged from 35 to 41%

| [29] | Kim, E., Chang, Y., Ko, J., Jeong, J., (2013) Physicochemical and microbial properties of the Korean traditional rice wine, Makgeolli, supplemented with banana during fermentation. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 18, 203–209. https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2013.42.10.1682 |

[29]

.

Mean value of crude fat, ash, moisture, protein, carbohydrates and energy were tabulated in (

table 1) of Korefe, borede and booka samples. Their chemical and nutritional properties were compared statistically and there was no significance (P < 0.05) difference for crude fat, ash, of all samples. The nutritional values of current traditional alcoholic beverages can be seen in two ways. In low alcoholic beverages, the nutritional values are higher than their respective raw materials. The main justification forwarded by authors is the live microorganisms present in these beverages. In high alcoholic beverages, the nutritional values are lower than that of low alcoholic traditional beverages

| [30] | Eskindir GF. Shimelis AE., Hundessa DD., Debebe WD., and Jae HS. (2020). Cereal- and Fruit-Based Ethiopian Traditional Fermented Alcoholic Beverages, Journal of foods. 9: 1781. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9121781 |

[30]

.

As shown in

Table 1, Borde, Shamita and Cheka have a good nutritional value compared to that of high alcoholic beverages like Tella and Teji. As the fermentation continues, from the fermentation dynamics point of view, only limited microorganisms withstand the adverse environmental effect of the growth medium. Thus, the microorganisms that do not cope with the new environment will be lysed and become a source of protein for cell maintenance for the surviving species. This analysis works even better in natural, spontaneous and uncontrolled fermentation systems. Hence, this competition in return decreases the nutritional value of the beverages while increasing secondary metabolites like ethanol

| [31] | Rajković, M.; Ivana D. Novaković, I.; Petrović, A. (2000). Determination of titratable acidity in white wine. Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 169-184. |

[31]

.

But, significantly higher concentration of CO

2 affects the growth and multiplication of yeast due to the formation of carbonic acid (HCO

3 - ions) that reduce the pH of the yeast medium, that make significantly low loads of yeast in Kochi than Merkato tella

| [32] | Kebede A, Fekadu B, Langsrud T, Narvhus J., (2002). Parameters of processing and microbial changes during fermentation of borde, a traditional Ethiopian beverage. J. Food Technol. Afr. 7(3): 85-92. https://doi.org//10.4314/jfta.v713.19238 |

| [34] | Adams MRO., (2008). Moss Food Microbiology. 3rd Ed. RSC Publishing. 9: 310- 369. |

| [35] | Tadele Y., Fekadu M., and Khalid S., (2013). Preparation and Physicochemical Analysis of Some Ethiopian Traditional Alcoholic Beverages. Global Journals of Food Science and Technology. 1(1): 88 – 90. |

[32, 34, 35]

. In this study, contents of CO

2 in collected tella were in range of EBC and Beddelle beer recommended.

Table 1. Results for nutritional values of traditional fermented beverages Borde, Booka and Korefe.

Nutritional values | Borde | Korefe | Booka |

Moisture (%) | 78.9±0.20 | 92.1±0.25 | 83.4±0.22 |

Ash (%) | 3.32±0.21 | 4.8±0.26 | 0.97±0.24 |

Protein (%) | 9.75±0.2 | 7.3±0.20 | 8.8±0.24 |

Fat (%) | 6.71±0.23 | 6.99±0.21 | 2.33±0.2 |

Carbohydrates (%) | 4.64 ±0.1 | 2.31±1.00 | 5.47±0.24 |

Energy (Cal) | 125.95±0.2 | 101.35±1.00 | 78.05±2.00 |

Values are Mean ±SD, triplicate analysis.

Borde had low pH values (< 4.2) with insignificant variation within samples (Coefficient of variation, CV, 5 - 11%) (

Table 1). A total of 322 isolates were obtained from countable PC plates in this study. The aerobic mesophilic flora was dominated by a variety of bacterial genera (

Table 3). The major genera that dominated borde were Bacillus, Micrococcus and Lactobacillus spp. Over a third of the total protein in both fermented beverages was soluble.

3.2. Microbial Activities of Borde, Korefe and Booka

The result of microbial activities such as E. Coli, Enterobacteriaceae, Lacobacillus and coliforms in borde, korefe and booka drink were 0.51, 1.67 ×10

1, 1.2 ×10

4, 3.67 ×10

5 respectively. According to Guesh M., and Anteneh T., 2017), report samples of tella from open markets at five localities in southern Ethiopia showed average aerobic Lactobacillus, bacillus and yeast counts of 9.9, 10.1, and 8.1 log cfu/g respectively, which was higher in current study

| [33] | Guesh M., and Anteneh T., (2017). Technology and microbiology of traditionally fermented food and beverage products of Ethiopia: A review, African Journal of Microbiology Research. 11(21): 825-844. https://doi.org/10.AJMR2017.8524 |

[33]

. Mean microbial count values (log cfu/g) ranged from 4.87 to 5.18 for AMB, 2.02 to 2.50 for Enterobacteriaceae, 1.73 to 2.24 for coliforms, 2.46 to 3.04 for enterococci, 3.09 to 3.76 for staphylococci, 5.31 to 5.68 for LAB and 3.28 to 3.87 for yeasts

| [34] | Adams MRO., (2008). Moss Food Microbiology. 3rd Ed. RSC Publishing. 9: 310- 369. |

| [35] | Tadele Y., Fekadu M., and Khalid S., (2013). Preparation and Physicochemical Analysis of Some Ethiopian Traditional Alcoholic Beverages. Global Journals of Food Science and Technology. 1(1): 88 – 90. |

[34, 35]

.

The fermenting organisms were composed of Lactobacillus spp. (mostly Lactobacillus pastorianumi). The yeasts dominated the fermenting flora after the end of the first stage till the completion of fermentation. Increase in alcohol content was accompanied by yeast growth and decrease in reducing sugars and total carbohydrates. Therefore, this study shows that the alcoholic contents Booka (1.53±0.2) < Korefe (4.21±0.2) < Borede (4.67±0.2), this is due to the fermenting time during preparation. The pH and ethanol content are in the range of 3.01- 4.10 and 1.53 – 4.67% (v/v) respectively. Tella is considered to range was 3.93 – 4.20 and 4.33 – 5.20% v/v after ten days of fermentation, tella becomes too sour to consume due to the growth of Acetobacter spp. which convert ethanol to acetic acid under aerobic conditions, but in this study less Acetobacter spp was happened

| [11] | Fite, A., Tadesse, A., Urga, K., and Seyoum, E., (1991). Methanol, fuel oil and ethanol contents of some Ethiopian traditional alcoholic beverages. SINET. Ethiop J Sci. 14, 19-27. |

[11]

. According to Fite A.

et al. (1991)

| [11] | Fite, A., Tadesse, A., Urga, K., and Seyoum, E., (1991). Methanol, fuel oil and ethanol contents of some Ethiopian traditional alcoholic beverages. SINET. Ethiop J Sci. 14, 19-27. |

[11]

, tella collected from Debre Berhan, Ataye and Addis Ababa had alcohol content of 2.4-3.3%, 2.1-2.7% and 1.6-2.8%, respectively, which were less than in these study. Belachew D., 1977), in his survey of alcoholic content of some traditional beverages of Ethiopia, found that the ethanol content of tella ranged from 5.65% to 6.56%

| [36] | Belachew D., (1977). A survey of the alcoholic contents of traditional beverages. Ethiop. Med. J. 15, 65-68. |

[36]

.

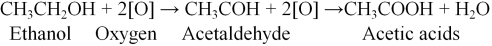

Low availability of oxygen inside the tank; may be oxidized ethanol to acetic acid, due to the growth of Acetobacter, which convert ethanol to acetic acid (Ethanoic acids) under aerobic condition as in reaction below

.

The average pH values of teji and araki (4.53 – 4.76 and 5.3 – 6.23) reported in Tadele Y.,

et al, 2013) was slightly higher than in current study (3.01 – 4.1). Whereas, alcoholic contents teji and araki (12.98 and 36.99) were far higher than I this study (4.67). However, the alcoholic contents reported in was 4.34 for ajip which is slightly similar in this study

.

Titratable acidity and pH indications of microbial growth, but in current study both are low i.e. acidic and TA was lower compared to other study. Decrement of TA was continued to the end and finally, TA was reached to 1.21 ± 0.2 to 0.29±0.2% lactic acid. The pH value was dropped from a value of 4.1±0.2 to 3.01 ± 0.2 at the end of first stage of fermenting Korefe. Other study suggests the indicated that the mean pH values of retail dry sausages ranged from 6.09 to 6.33, which is lower than in current study.

The aerobic mesophilic bacterial flora of retail in this study was dominated by Gram-positive bacteria. E. coli and LAB was isolated from two all samples. Spoilage of all samples after the package was opened, was detected within 3 to 4 days for borede but for booka and korefe 6 to 10 days during aerobic storage at ambient temperature (22 °C on average) and within 4 to 5 days for borede and 15 to 30 days for booka and korefe at refrigeration storage (4 °C). Generally, the majority of retail in all sample showed the presence of microbial load, which indicated contamination during or after processing of the products (

Table 2).

Safety is the most pre requesting criteria for all drinking. Most study lacks this criteria, but in current study all samples borede, korefe and booka were properly prepared and no effects on human consumptions because of less fermentation time. Therefore, all parameters such as time, temperature, moisture content, pH and TA changes were monitored during the spontaneous fermentation of korefe, borede and booka at every 3 h intervals

| [40] | Nout MJR. (2008). Microbiological aspects of the traditional manufacture of Busaa, a Kenyan opaque maize beer. Chern Mikrobiol Technol Lebensm. 6: 137-42. |

[40]

.

Table 2. Effects of microbial activity on fermented Borde, Booka and Korefe during 1 months of study.

Parameters and microbes | Borde | Korefe | Booka |

pH | 3.9±0.10 | 4.1±0.20 | 3.01±0.25 |

Titratable Acidity (TA) | 0.29±0.20 | 0.34±0.33 | 1.21±0.20 |

Alcoholic Contents,% (v/v) | 4.67±0.22 | 4.21±0.2 | 1.53±0.24 |

E. Coli (CFU/ml) | 0.51±0.20 | 0.11±0.21 | 0.41±0.20 |

Enterobacteriaceae (CFU/ml) | 1.67 ×101 | 0.34×103 | 0.13 ×102 |

Lactobacillus (CFU/ml) | 1.2 ×104 | 0.22×103 | 0.07 ×103 |

Coliforms (CFU/ml) | 3.67 ×105 | 0.02×103 | 1.67 ×101 |

The values in the table are the mean of triplicates with standard deviation (±) for (TA, pH and Alcoholic content). Mean values in the column are not significantly different (P ≤ 0.05).

3.3. Organoleptic Properties of Borde, Korefe and Booka

The results of this study showed that biscuits produced from SFPC had very high acceptable values of all the sensory attributes comparing with biscuit control, even though biscuit prepared from wheat flour had slightly higher scores in terms of flavor (9.00). All the sensory attributes were non-significant difference (p ≥ 0.05) compared to wheat control biscuit as well as among inclusion levels.

Table 3. Organoleptic evaluation of Borede, Booka and Korefe traditional food.

Organoleptic | Borde | Korefe | Booka |

Color | 1.56±0.5a | 6.66±0.9b | 5.72±0.9c |

Flavors | 2.42±0.7b | 2.09±0.4a | 3.03±0.4c |

Odors | 3.02±1.0b | 2.17±0.1a | 3.00±0.54c |

Test | 3.25±2.0c | 2.78±0.7b | 4.00±0.5a |

Bitter | 1.44±0.7b | 4.44±0.6a | 3.56±0.7a |

Sour | 1.99±0.8c | 1.82±0.6b | 2.79±1.0a |

The values in the table are the mean of triplicates with standard deviation (±). Mean values followed by the same letter in the column are not significantly different (P≤ 0.05).

Addition of sorghum to wheat flour improved all organoleptic characteristics of borede, booka and korefe. booka and korefe samples slightly higher mean scores in terms of color 5.72 ±0.9, 6.66±0.9, while borede samples had slightly lower scores in terms of color (1.56±0.5), bitter (1.44±0.7). From this data, it can be noticed that, incorporating of honey had slightly lower score on color of booka comparing with korefe and borede by flavors and taste as in

table 3 above; that could be due to protein and fat content differences.

Total Carbohydrate content of Booka; lower content of were recorded for Booka but the differences were not statistically different from carbohydrate content of Cheqa (in Derashe), Booka and Korefe in Guji and Borana and Bordaa (in Burji) p=0.547 and p=0.207 respectively. Alongside that of mean variation there is a significant difference of mean in comparison to the other locally consumed traditional drinking. Whereas for Overall acceptability content of Booka was significantly different for other type of traditional drinking documented in different areas of Ethiopia

| [18] | Akinrele IA., (1970). Fermentation studies on maize during the preparation of a traditional African starch-cake food. Journals of Science and Food Agriculture. 21, 619¬. https://doi.org/10.12691/ajfst-2-5-3 |

[18]

. Adjacent to that, it is known that the booka might indicate that the presence of minerals in food sample. This might support the generation of hypothesis to be developed further because of supported by indigenous knowledge of Gujii elders that believed the consumption of booka, korefe and bored increase the strength of Bone and in all other parts

| [41] | Agren G., and Gibson R., (2008). Food Composition Table for Use in Ethiopia 1. CNU report No. 16. |

[41]

.