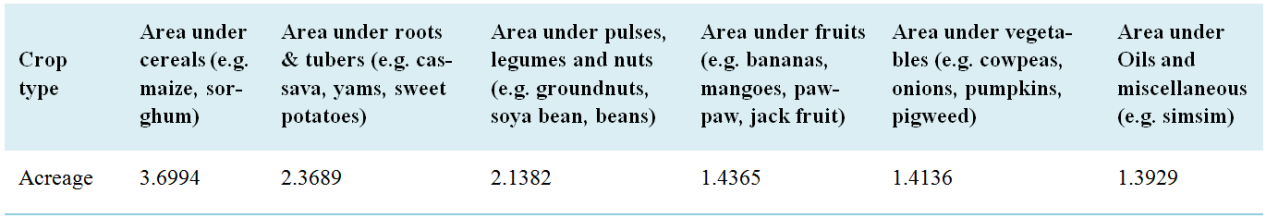

Food insecurity is a major problem in Busia County as studies show that 54 percent of households face food insufficiency and child malnutrition. This problem is compounded by small land holdings per household, with just 155,990 acres under food crops. Studies that have been done in the County to show the major food crops that are cultivated, however, no single one has been done showing the variations of these food crops within regions, while it is well known that diversity in terms of space has a bearing in food security at household level. This research sought to find out how food crops are diversified within space and its implications on household food security. Mixed design approach was used (descriptive and correlational). Nine research assistants were involved to collect data in the cropping season using interview schedules and observation schedules. Primary data was collected in one cropping season using interview and observation schedules. Gibbs and Martins Index of crop diversification was applied to determine crop diversification. Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS) was used to determine food security status. Multi-stage mixed sampling techniques involving purposive, simple random stratified proportionate was used. Qualitative data was used to address research questions while quantitative data addressed the hypotheses. The results showed that there was a wide range of food crops grown in the County with cereals taking the largest portion while oils and miscellaneous crops had the lowest acreage. The study further revealed that Busia County had household food security index of 3.52 in the range of 1 to 6. It also found no statistically significant difference in regional diversification of food crops (p= .126). Finally, it revealed a very low negative correlation (r= -.080) with an insignificant relationship (p= .13) between crop diversification and household food security.

| Published in | World Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology (Volume 2, Issue 2) |

| DOI | 10.11648/j.wjast.20240202.13 |

| Page(s) | 54-68 |

| Creative Commons |

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited. |

| Copyright |

Copyright © The Author(s), 2024. Published by Science Publishing Group |

Spatial Analysis, Crop Diversification, Food Crops, Food Security, Busia County

Characteristic | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

Sub-county (n=384) | ||

Butula | 129 | 33.6 |

Bunyala | 129 | 33.6 |

Teso South | 126 | 32.8 |

Total | 384 | 100.0 |

Ward (n=384) | ||

Kingandole | 43 | 11.2 |

Marachi Central | 43 | 11.2 |

Elugulu | 43 | 11.2 |

Bwiri | 43 | 11.2 |

Ageng'a Nanguba | 43 | 11.2 |

Nangina | 43 | 11.2 |

Chakol South | 43 | 11.2 |

Chakol North | 43 | 11.2 |

Ang'orom | 40 | 10.4 |

Total | 384 | 100.0 |

Household head (n=380) | ||

Father | 279 | 73.4 |

Mother | 89 | 23.4 |

Child-headed | 12 | 3.2 |

Total | 380 | 100.0 |

Level of education of household head (n=384) | ||

Didn't complete class 8 | 89 | 23.2 |

Kenya Certificate of Primary Education (KCPE) | 213 | 55.5 |

Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education (KCSE) | 67 | 17.4 |

College graduate | 9 | 2.3 |

University graduate | 6 | 1.6 |

Total | 384 | 100.0 |

Household size (n=384) | ||

1-3 | 82 | 21.4 |

4-6 | 188 | 49.0 |

7-10 | 81 | 21.1 |

> 10 | 33 | 8.6 |

Total | 384 | 100.0 |

Family land size in acres (n=384) | ||

< 0.49 | 23 | 6.0 |

0.5-1.49 | 95 | 24.7 |

1.5-2.99 | 100 | 26.0 |

3-4.49 | 79 | 20.6 |

> 4.5 | 87 | 22.7 |

Total | 384 | 100.0 |

Land size on food crops (n=380) | ||

< 0.25 | 24 | 6.3 |

0.25-0.49 | 19 | 5.0 |

0.5-0.99 | 82 | 21.6 |

1-1.25 | 14 | 3.7 |

>1.25 | 241 | 63.4 |

Total | 380 | 100.0 |

Land ownership (n=374) | ||

Collective/communal | 23 | 6.1 |

Individual | 351 | 93.9 |

Total | 374 | 100.0 |

Land registration status (n=368) | ||

Titled | 222 | 60.3 |

Not titled | 146 | 39.7 |

Total | 368 | 100.0 |

Item | Response | Likelihood | Response | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

No | Not sure | Yes | Total | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Total | |||

In the past 24 hours, did you worry that your household would not have enough food? | n | 203 | - | 181 | 384 | How often it happened | 99 | 70 | - | 177 |

f | 52.9 | 47.1 | 100 | 59.9 | 39.5 | 4.5 | 100 | |||

In the past 24 hours, were you or any household member not able to eat the kinds of foods you preferred because of a lack of resources? | n | 174 | 210 | 384 | How often it happened | 92 | 100 | 18 | 210 | |

f | 45.3 | 54.7 | 43.8 | 47.6 | 8.6 | 100 | ||||

In the past 24 hours, did you or any household member have to eat some foods that you really did not want to eat because of a lack of resources to obtain other types of food? | n | 234 | 150 | 384 | How often it happened | 68 | 77 | 5 | 150 | |

f | 60.9 | 39.1 | 100 | 45.3 | 51.3 | 3.3 | 100 | |||

In the past 24 hours, did you or any household member have to eat a smaller meal than you felt you needed because there was not enough food? | n | 282 | 102 | 384 | How often it happened | 45 | 52 | 5 | 102 | |

f | 73.4 | 26.6 | 100 | 44.1 | 51.0 | 4.9 | 100 | |||

In the past 24 hours, did you or any other household member have to eat fewer meals in a day because there was not enough food? | n | 198 | 10 | 169 | 377 | How often it happened | 78 | 100 | 8 | 186 |

f | 52.5 | 27 | 44.8 | 100 | 41.9 | 53.8 | 4.3 | 100 | ||

In the past 24 hours, was there ever no food to eat of any kind in your household because of lack of resources to get food? | n | 286 | 86 | 372 | How often it happened | 4 | 4 | |||

f | 76.9 | 23.1 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |||||

Food class variation | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

4 types | 154 | 42.2 |

3 types | 79 | 21.6 |

2 types | 65 | 17.8 |

5 types | 55 | 15.1 |

1 type | 9 | 2.5 |

All (6) types | 3 | .8 |

Total | 365 | 100.0 |

Area under various crop types | Count | Response range (land size in acres) | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

< 0.25 | 0.25-0.49 | 0.5-0.99 | 1-1.25 | >1.25 | |||

Cereals (e.g. maize, sorghum) | n | 25 | 28 | 93 | 54 | 126 | 326 |

f | 7.7 | 8.6 | 28.5 | 16.6 | 38.7 | 100 | |

Roots & tubers (e.g. cassava, yams, sweet potatoes) | n | 105 | 78 | 82 | 45 | 18 | 328 |

f | 32.0 | 23.8 | 25.0 | 13.7 | 5.5 | 100 | |

Vegetables (e.g. cowpeas, onions, pumpkins, pigweed) | n | 195 | 78 | 22 | - | - | 295 |

f | 66.1 | 26.4 | 7.5 | - | 100 | ||

Fruits (e.g. bananas, mangoes, pawpaw, jack fruit) | n | 183 | 41 | 15 | 13 | - | 252 |

f | 72.6 | 16.3 | 6.0 | 5.2 | - | 100 | |

Pulses, legumes and nuts (e.g. groundnuts, soybean, beans) | n | 92 | 41 | 53 | 24 | 7 | 217 |

f | 42.4 | 18.9 | 24.4 | 11.1 | 3.2 | 100 | |

Oils and miscellaneous (e.g. simsim) | n | 17 | 11 | - | - | - | 28 |

f | 60.7 | 39.3 | - | - | - | 100 | |

N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

How many types of food did your household consume in the last 24 hours (in the category of: cereals, roots and tubers, vegetables, fruits, pulses, legumes and nuts, oils and miscellaneous) | 365 | 1.00 | 6.00 | 3.5205 |

Valid N (list wise) | 365 |

Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Between Groups | 1.885 | 8 | 15.043 | 2.351 | .126 |

Within Groups | 2361.097 | 369 | 6.399 | ||

Total | 2376.140 | 377 |

Diversity index | Pearson Correlation | 1 | -.080 |

Sig. (2-tailed) | .131 | ||

N | 371 | 356 | |

Household food security | Pearson Correlation | -.080 | 1 |

Sig. (2-tailed) | .131 | ||

N | 356 | 365 |

HDDS | Household Dietary Diversity Score |

GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

SSA | Sub-Saharan Africa |

CDI | Crop Diversification Index |

ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

KCPE | Kenya Certificate of Primary Education |

KCSE | Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education |

| [1] | USAID. (2023). Agriculture, Food and Water Security. Washington DC: United States Agency For International Development. |

| [2] | United Nations Kenya (2023). Our Work on the Sustainable Development Goals in Kenya. Nairobi: United Nations. Retrieved from |

| [3] | Adjimoti, G. O., Kwadzo, G. T. M. (2018). Crop diversification and household food security status: evidence from rural Benin. Agric & Food Secur 7, 82 |

| [4] | World Bank. (2019). Kenya Economic Update: Transforming Agricultural Productivity to Achieve Food Security for All. Retrieved from |

| [5] | IFAD (2022). Investing in rural people in Kenya. Retrieved from |

| [6] |

Busia County Government. (2018). County Integrated Development Plan 2018-2022. Retrieved from

https://www.devolution.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Busia-CIDP-2018-2022.pdf |

| [7] | Republic of Kenya (2016). Busia County Biodiversity Policy. Busia: the county government of busia. |

| [8] |

Adeleke S., Abdul, B. K, & Zuzana B. (2010). Smallholder Agriculture in East Africa: Trends, Constraints and Opportunities. African Development Bank Group. Retrieved from

https://www.afdb.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/working_105_pdf_d.pdf |

| [9] | Manana, M. N. G. (2014). Challenges faced in the management of small scale farm enterprises in trans-nzoia county, Kenya. International Journal of Advanced Rsearch, volume 2, issue 7 845-950. |

| [10] | Makate C, Wang R, Makate M, Mango N. Crop diversification and livelihoods of smallholder farmers in Zimbabwe: adaptive management for environmental change. Springer Plus. 2016; 5(1): 1 18. |

| [11] | Mango, N. (2018). The role of crop diversification in improving household food security in central Malawi. Retrieved from |

| [12] | Di Falco S, Chavas J. P. On crop biodiversity, risk exposure and food security in the highlands of Ethiopia. Am J Agric Econ. 2009; 91(3): 599–613. |

| [13] | Appiah-Twumasi, M. & Asale, M. A. (2022). Crop diversification and farm household food and nutrition security in Northern Ghana. Environ Dev Sustain. 2022 Oct 15: 1 29. Retrieved from |

| [14] | Kundu, K., & Chattopadhyay, A. K. (2018). Spatio-temporal Variations of Crop Diversification. A Block-level Study in West Bengal. Economic and Political weekly. Vol 53. 21. Retrieved from |

| [15] | Gogoi, M. (2018). An Analysis of Spatio-Temporal Changes in the Pattern of Crop Diversification in Undivided Sivasagar District, Assam (India). Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research (JETIR). Volume 5, Issue 11. Retrieved |

| [16] | Hernández-Ochoa, I. M., Gaiser, T., Kersebaum, K., Webber, H., Seidel, S. J. Grahmann, K., & Ewert, F. Model-based design of crop diversification through new field arrangements in spatially heterogeneous landscapes. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 2022, 42 (4), pp. 74. |

| [17] |

Samanthi. (2020). Difference Between Temporal and Spatial Heterogeneity. Retrieved from

https://www.differencebetween.com/difference-between-temporal-and-spatial-heterogeneity/ |

| [18] | FAO. (2017). The future of food and agriculture. Trends and challenges. Rome: FAO. Retrieved from |

| [19] | Maritim, N. & Nick, D. (2021). The key to food security is crop diversification. Farm Kenya. The standard, Jan 05, 2021. Retrieved from |

| [20] | FAO. (2008). An Introduction to the Basic Concepts of Food Security. Rome: EC-FAO Food Security Programme. Retrieved from |

| [21] | Herforth, A. W. (2010). Promotion of traditional African vegetables in Kenya and tanzania: a case study of an intervention representing. Cornell University; 2010. |

| [22] | Furman, B., Noorani, A., and Mba, C. (2021). On-Farm Crop Diversity for Advancing Food Security and Nutrition. Retrieved from |

| [23] | MoALF. 2016. Climate Risk Profile for Busia. Kenya County Climate Risk Profile Series. The Kenya Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries (MoALF), Nairobi, Kenya. |

| [24] | Romanchuk, J. (2023). The Four Types of Research Design Everything You Need to Know. Retrieved from |

| [25] | Bakhsh, A. (2023). Purpose of correlational research. Retrieved from |

| [26] |

Gerald, J., & Dorothy, R. (2023). Household dietary diversity Score (HDDS). Retrieved from

https://inddex.nutrition.tufts.edu/data4diets/indicator/household-dietary-diversity-score-hdds |

| [27] |

Agriculture and Food Authority (2024). Food crops: overview. Retrieved from

https://food.agricultureauthority.go.ke/index.php/sectors/overview |

| [28] |

Kenya News Agency (2024). Root & Tuber Crops Important In Building Resilience In Food System. Retrieved from

https://www.kenyanews.go.ke/root-tuber-crops-important-in-building-resilience-in-food-system/ |

| [29] |

Biovision Africa Trust. (2024). Traditional starch sources for food and nutrition security. Retrieved from

https://theorganicfarmer.org/traditional-starch-sources-for-food-and-nutrition-security/ |

| [30] | Tadese, K. T. (2023). The Role of Vegetables in Ensuring Food Security and Poverty Alleviation: The Case of Ethiopia. J Nutr Food Sci, Vol. 13 Iss. 3 No: 1000020. Retrieved from |

| [31] |

Greenlife Crop Protection Africa. (2024). The role of pulses in offering food security. Retrieved from

https://www.greenlife.co.ke/the-role-of-pulses-in-offering-food-security/ |

| [32] |

Government of Kenya (2014). Agricultural Sector Development Support Programme (ASDSP). Volume 1. Household baseline survey report Busia County. Retrieved from

https://www.kalro.org/kalroknowledgebank/doc/Busia%20Volume%201%20HH%20Baseline-1.pdf |

| [33] | Nutrition in City Ecosystems. (2024). City Overview on Food and nutrition of: Busia City, Kenya. Retrieved from |

APA Style

Odhiambo, O. P., Njeri, N. M., Maingi, M. M. (2024). Spatial Analysis of Food Crop Diversification in Busia County-Kenya: Implications on Household Food Security. World Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology, 2(2), 54-68. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.wjast.20240202.13

ACS Style

Odhiambo, O. P.; Njeri, N. M.; Maingi, M. M. Spatial Analysis of Food Crop Diversification in Busia County-Kenya: Implications on Household Food Security. World J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2024, 2(2), 54-68. doi: 10.11648/j.wjast.20240202.13

AMA Style

Odhiambo OP, Njeri NM, Maingi MM. Spatial Analysis of Food Crop Diversification in Busia County-Kenya: Implications on Household Food Security. World J Agric Sci Technol. 2024;2(2):54-68. doi: 10.11648/j.wjast.20240202.13

@article{10.11648/j.wjast.20240202.13,

author = {Ongang’a Peter Odhiambo and Ngugi Margaret Njeri and Mwatu Morris Maingi},

title = {Spatial Analysis of Food Crop Diversification in Busia County-Kenya: Implications on Household Food Security

},

journal = {World Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology},

volume = {2},

number = {2},

pages = {54-68},

doi = {10.11648/j.wjast.20240202.13},

url = {https://doi.org/10.11648/j.wjast.20240202.13},

eprint = {https://article.sciencepublishinggroup.com/pdf/10.11648.j.wjast.20240202.13},

abstract = {Food insecurity is a major problem in Busia County as studies show that 54 percent of households face food insufficiency and child malnutrition. This problem is compounded by small land holdings per household, with just 155,990 acres under food crops. Studies that have been done in the County to show the major food crops that are cultivated, however, no single one has been done showing the variations of these food crops within regions, while it is well known that diversity in terms of space has a bearing in food security at household level. This research sought to find out how food crops are diversified within space and its implications on household food security. Mixed design approach was used (descriptive and correlational). Nine research assistants were involved to collect data in the cropping season using interview schedules and observation schedules. Primary data was collected in one cropping season using interview and observation schedules. Gibbs and Martins Index of crop diversification was applied to determine crop diversification. Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS) was used to determine food security status. Multi-stage mixed sampling techniques involving purposive, simple random stratified proportionate was used. Qualitative data was used to address research questions while quantitative data addressed the hypotheses. The results showed that there was a wide range of food crops grown in the County with cereals taking the largest portion while oils and miscellaneous crops had the lowest acreage. The study further revealed that Busia County had household food security index of 3.52 in the range of 1 to 6. It also found no statistically significant difference in regional diversification of food crops (p= .126). Finally, it revealed a very low negative correlation (r= -.080) with an insignificant relationship (p= .13) between crop diversification and household food security.

},

year = {2024}

}

TY - JOUR T1 - Spatial Analysis of Food Crop Diversification in Busia County-Kenya: Implications on Household Food Security AU - Ongang’a Peter Odhiambo AU - Ngugi Margaret Njeri AU - Mwatu Morris Maingi Y1 - 2024/05/30 PY - 2024 N1 - https://doi.org/10.11648/j.wjast.20240202.13 DO - 10.11648/j.wjast.20240202.13 T2 - World Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology JF - World Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology JO - World Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology SP - 54 EP - 68 PB - Science Publishing Group SN - 2994-7332 UR - https://doi.org/10.11648/j.wjast.20240202.13 AB - Food insecurity is a major problem in Busia County as studies show that 54 percent of households face food insufficiency and child malnutrition. This problem is compounded by small land holdings per household, with just 155,990 acres under food crops. Studies that have been done in the County to show the major food crops that are cultivated, however, no single one has been done showing the variations of these food crops within regions, while it is well known that diversity in terms of space has a bearing in food security at household level. This research sought to find out how food crops are diversified within space and its implications on household food security. Mixed design approach was used (descriptive and correlational). Nine research assistants were involved to collect data in the cropping season using interview schedules and observation schedules. Primary data was collected in one cropping season using interview and observation schedules. Gibbs and Martins Index of crop diversification was applied to determine crop diversification. Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS) was used to determine food security status. Multi-stage mixed sampling techniques involving purposive, simple random stratified proportionate was used. Qualitative data was used to address research questions while quantitative data addressed the hypotheses. The results showed that there was a wide range of food crops grown in the County with cereals taking the largest portion while oils and miscellaneous crops had the lowest acreage. The study further revealed that Busia County had household food security index of 3.52 in the range of 1 to 6. It also found no statistically significant difference in regional diversification of food crops (p= .126). Finally, it revealed a very low negative correlation (r= -.080) with an insignificant relationship (p= .13) between crop diversification and household food security. VL - 2 IS - 2 ER -